An abdominoplasty is a surgical procedure that recontours the abdomen. This is achieved by addressing several issues:

- Removing excess skin and subcutaneous fat of the abdomen

- Tightening lax abdominal musculature (usually a result of pregnancy)

- Rejuvenating the mons (the area of hair bearing skin above the genitals

- Narrowing the waistline

- Smoothing the lateral contour of the trunk

- Removing excess skin and fat in the flanks and back (in extended and circumferential procedures only)

Abdominoplasty is different from liposuction. Liposuction is a procedure that removes only excess subcutaneous (below the surface of the skin) fat, however, excess skin is not removed. Since 1990, when I was a resident in plastic surgery, up to the present time, I have seen many changes in both liposuction and abdominoplasty. These two procedures became more and more refined, yielding better and better results, with less discomfort and downtime, as well as a greater margin of safety. What I find most interesting, is that each of these procedures developed and matured, independent of the other. Also of note is the fact that in the past, a patient would undergo either abdominoplasty or liposuction, but not both at the same time, to re-contour the trunk. Now, it is more common among a select number of surgeons to utilize both techniques simultaneously to create a more comprehensive restorative plan to rejuvenate the trunk. This is discussed in the section:

Removing Excess Skin and Subcutaneous Fat of the Abdomen

The best patient for liposuction has minimal excess skin but has excess subcutaneous fat and the best patient for an abdominoplasty has the opposite situation: minimal excess fat but does have a significant excess of abdominal skin. This doesn’t mean that a patient is not a candidate for an abdominoplasty if the also have excess subcutaneous fat, or a patient is not a candidate for liposuction if they have some excess skin, I am just speaking in terms of the most ideal of circumstances. Many patients who obtain wonderful results from both surgeries do not fall at the far ends of the spectrum. Later on, I will discuss how the two procedures, liposuction and abdominoplasty may be combined during the same surgical procedure to get the most optimal results in patients who have BOTH an excess of skin and an excess of fat, which is the case in the vast majority of my patients who present to me for rejuvenation of their abdomen. This procedure is called a 4D VASER Lipoabdominoplasty.

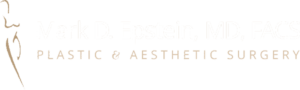

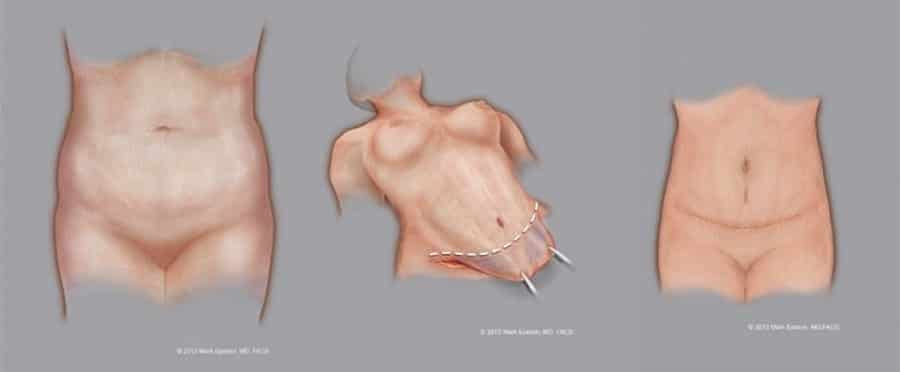

Figure 1 – Click to Enlarge – Left: Excess fat, Middle: Excess skin and fat, Right: Excess skin

Figure 1 – The spectrum of balance between excess skin and fat – The patient represented by the left figure would probably be best contoured with liposuction, as her problem is mostly excess fat with little excess skin. If an abdominoplasty is performed, little excess skin will be removed and the overall appearance will not be significantly changed. The patient on the right, however, would probably be best served undergoing an excisional procedure such as an abdominoplasty. Liposuction alone will not deal with all the excess skin. The patient in the middle has more excess skin than the patient on the left, but not as much as the patient on the right. It is a judgment call in these cases, and sometimes, neither abdominoplasty nor liposuction will be clearly indicated over the other. In these cases, the surgeon must determine what bothers the patient the most, how the patient feels about the resultant scars and give the patient several options. This patient would be an excellent candidate for a 4D VASER Lipoabdominoplasty. NOTE: While the patient on the right mainly suffers from an excess of skin and could be treated with an abdominoplasty alone, this patient would also attain better results with a 4D VASER Lipoabdominoplasty, as there is still excess fat that should be removed as well. The rationale for this will be addressed later on in the 4D VASER Lipoabdominoplasty section.

The Incision

The incision for an abdominoplasty is typically placed in the waist crease, sometimes a little lower. The incision is made down to the abdominal muscles and then the skin is elevated upwards. In all types of abdominoplasties with the exception of the mini-abdominoplasty, the skin is elevated above the umbilicus (the navel) up towards the lower margin of the rib cage. When this is done, an incision must be made around the umbilicus so as to keep the umbilicus attached to the muscles as the skin is elevated upwards above it.

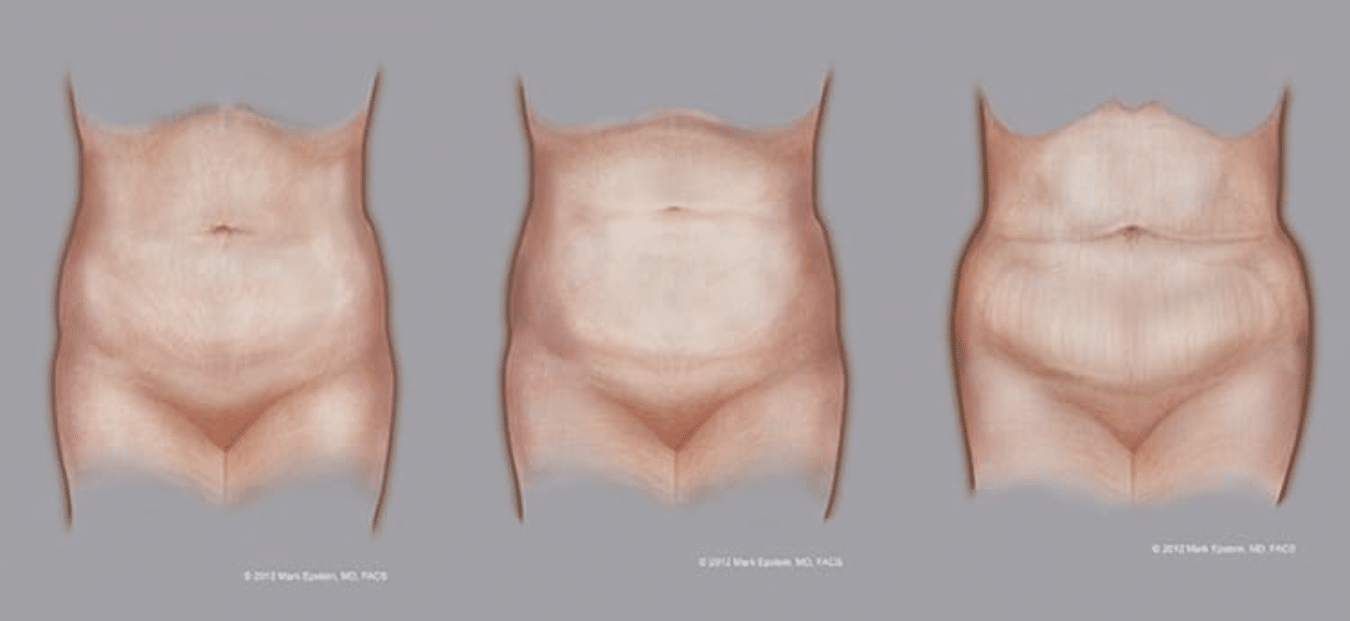

Figure 2 – Variations in skin elevation – Two variations of abdominoplasty. In both examples, the incision in the waist crease and around the umbilicus are the same. The difference is that the example on the left includes wide “undermining” or elevation of the skin off the abdominal wall muscles. This mobilizes a great deal of abdominal skin, but at the cost of decreasing the blood supply and innervation (supply of sensation via sensory nerves) to the abdominal skin. In some cases, this may result in difficulties with wound healing, although in non-smokers, this is rarely the case. There is also a larger “dead space”, the space betwen the abdominal wall muscles and the undersurface of the overlying skin, and more fluid may accumulate there. The example on the right is one of “limited undermining” in which more of the circulation and innervation is preserved, with less dead space. The benefit is greater margin of safety with regard to maintaining blood supply to the skin to prevent wound healing problems, better preservation of sensation and a lower risk of accummulation of fluid betwen the skin and the underlying muscles during the postoperative period. The extent of lateral (sideways) undermining required depends upon the laxity and thickness of the overlying skin. I prefer to keep the lateral undermining to the absolute minimum that I can and still get proper re-draping of the skin over the abdominal wall musclulature for all the reasons discussed above.

Tightening Lax Abdominal Musculature

A developing fetus is a powerful force acting upon the abdominal musculature, slowly causing the abdominal wall to stretch over the nine month gestational period. Changes in hormone balance during pregnancy also act to facilitate the ability of the body’s tissues to stretch, preparing the woman’s body for the future birth of her child. I don’t want my male patients to feel left out at this juncture, I am just addressing this portion of the discussion to the ladies because men do not experience pregnancy. When I am recontouring a male abdomen, in almost all circumstances, the abdominal wall does not require tightening. The exception to this might be a patient who has experienced massive weight loss.

Now here’s the myth – the muscles don’t really get tightened! We use the term “tightening the muscles”, I have certainly been guilty of using this term because in a lay sense, patients know what I am talking about – making their abdominal wall tighter. I usually then go into greater anatomical detail with my patients as I will here.

First: a brief anatomy lesson. The abdominal wall is made up of several muscles: the Rectus Abdominus, External Oblique, Internal Oblique and Transversus abdominus muscles. The Rectus Abdominus muscles are a pair of vertical muscles that measure approximately four inches wide and run from the underside of the rib cage to the pelvis, traversing the entire abdomen. There are three “tendinous inscriptions” or pleats in the muscle that run horizontally. These pleats are what divide the muscle up into sections which have been termed “the six pack”. Whether or not you can see those pleats depends on the thickness of the skin and fat overlying the muscle as well as how well the muscle itself is developed. The muscles lie side by side and are separated by approximately 1 – 2 cm. On the lateral (outer) sides of these muscles lie the Internal Oblique and External Oblique muscles whose fibers run, as their name states, obliquely (at an angle) from the side of the trunk to the Rectus Abdominus and from the ribs to the pelvis. Underneath the pblique muscles lie the transversus abdominus muscles.

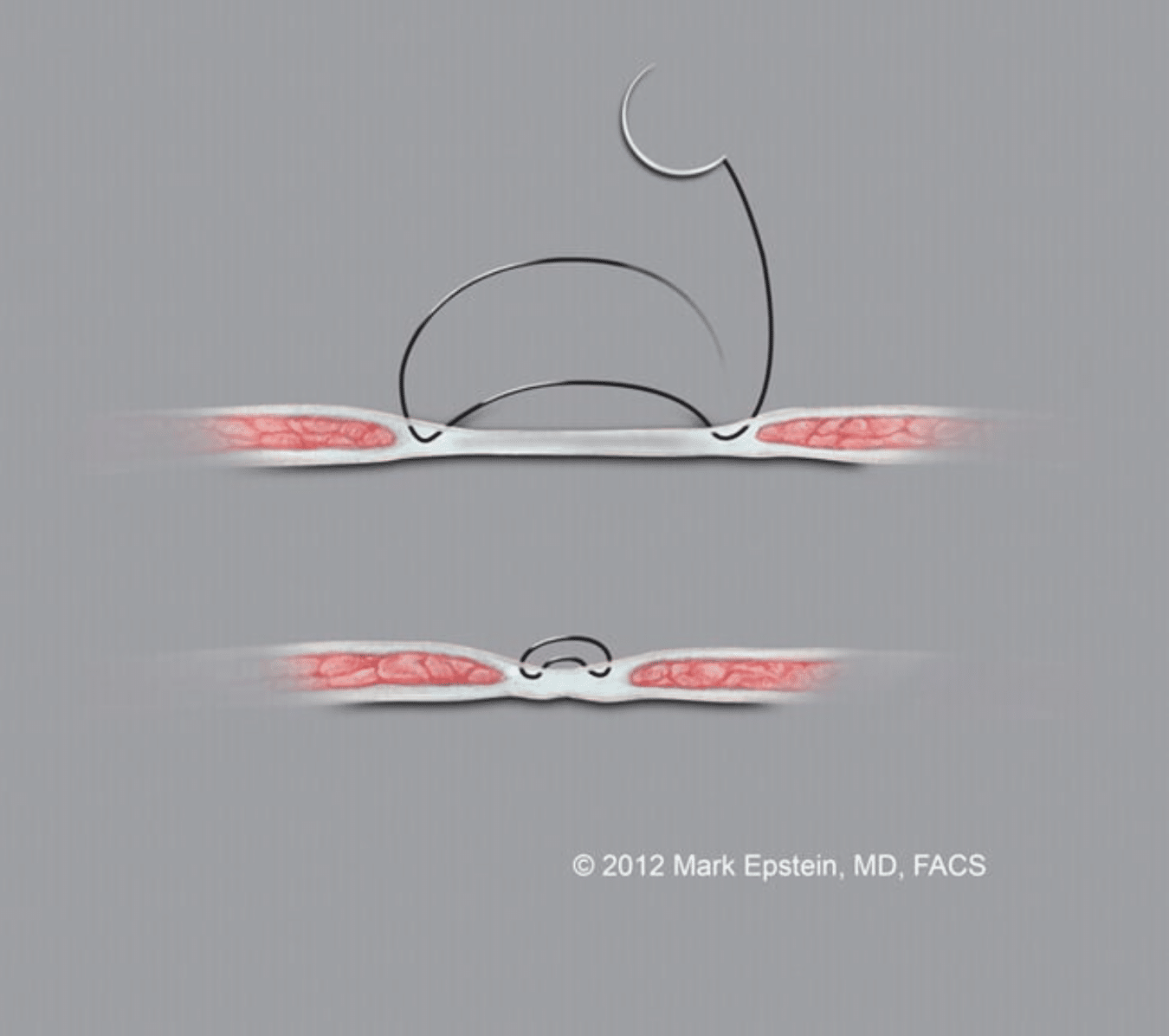

The abdominal muscles are enveloped, or wrapped by an investing fascia. Fascia is a thin, but strong sheet of tissue that covers the surfaces of muscles and other structures in the body. Although not very interesting to some anatomists, fascia is of paramount importance to surgeons because it is the fascia that is strong enough to hold sutures (stitches) placed during surgery. You may say “muscles are strong, why not place sutures in the muscles”? The fact is, although a contracting muscle generates a lot of force, the muscle tissue itself is not really good at holding sutures. The sutures will just pull right through the muscle tissue. Below is a diagram of how it all fits together. This diagram is what we call a “cross-sectional view.” Imagine cutting through the abdominal wall from right to left and then looking at the edge of the tissue, again from left to right. This diagram shows the relationship between the muscles and the fascia. The fascia covers the muscles from above and below, but it is the fascia above the muscle that is of greatest thickness and strength and is what surgeons rely upon to tighten the abdominal wall.

Figure 3 – Click to Enlarge

Figure 3: Abdominal wall cross section showing relationship of muscles and fascia – The sutures are shown placed into the muscle fascia to provide tightening of the abdominal wall

During pregnancy, the fascia and the muscles get stretched. After pregnancy, the tissues try to come back to the way they were, but this doesn’t quite happen completely. The woman’s genetic predisposition, the size of the fetus, the elasticity of her abdominal wall tissue itself and other factors determine just how much the abdominal wall will revert to its pre-pregnancy state. This is somewhat (loosely) analogous to the elastic waistband on a pair of underwear. Depending upon the quality and age of the elastic, how many times it has been worn, how much you need to “squeeze” into that pair of underwear to wear it, determines how much elasticity is lost and how lax that band of elastic will become. In the case of the pregnant abdomen, and this point is very important, the fascia between the Rectus Abdominus muscle stretches and the muscles separate. When the separation is significantly wide, it is called a “diastasis”. When this occurs, the abdomen actually appears to protrude forward, often causing great concern to the woman.

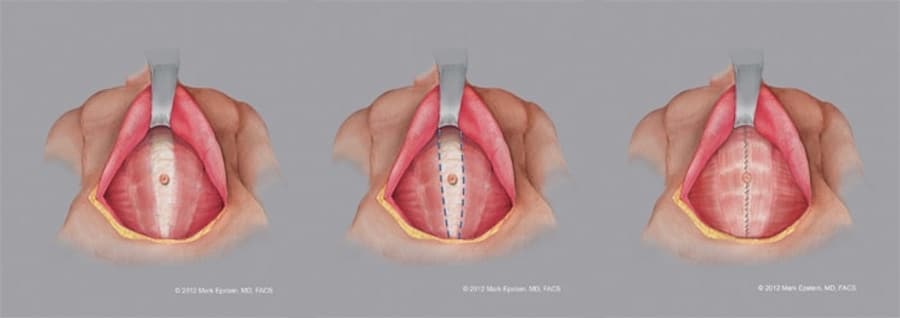

So how do surgeons “tighten the muscles”? This is actually quite simple. After the skin is lifted off the abdominal wall, the area of the diastasis is well exposed. Many sutures are placed from right to left across the midline to pull the excess fascia above the muscles (this is called the Anterior Rectus sheath) together, creating one very long vertical pleat from rib cage to pelvis (the pubic bone of the pelvis to be exact). The action of this narrows the width of the abdominal wall by pulling it in from the sides. This helps to narrow the waistline, as well as to reduce the amount of protrusion of the abdomen anteriorly (to the front).

Figure 4 – Click to Enlarge

Figure 4: Plicating (tightening) the muscle fascia of the abdominal wall

Removing The Excess Skin

After the abdominal wall skin has been elevated off the abdominal wall musculature and the abdominal muscles tightened, the next step is the removal of the excess abdominal skin. The amount of skin that can be removed depends upon the amount of skin excess. This certainly makes sense. There is a “wrinkle”, however. Think of the abdomen as two regions, the supraumbilical region of the abdomen (between the rib cage and the umbilicus) and the infraumbilical region of the abdomen (between the umbilicus and the lower waist crease incision). Remember that hole that was created in the abdomimal skin from cutting around the umbilicus? If the abdominal skin can be pulled so far downward that the hole is now below the level of the waist crease incision, then there is no hole remaining after the excess abdominal skin is removed and therefore no scar from this hole. That is the “ideal” situation. However, sometimes, there is not enough upper abdominal skin excess (the lower abdominal skin excess does not matter here) to advance the hole downward below the level of the waist crease incision. In this case, the hole will remain above the waist crease incision, sometimes just above it, and sometimes somewhere between the waist crease incision and the new location of the umbilicus (which is still attached to the abdominal muscles). If the hole is above the waist crease incision, then it is closed with sutures and will remain as a small vertical incision on the lower abdomen. As long as this vertical incision lies below the waistband of clothing, it will not be visible. In an effort to avoid this little vertical scar, some surgeons start with a higher waist crease incision. The problem with this approach is that although there may be no small vertical scar, the transverse waist crease incision may be visible, in whole or in part, above the waistband of clothing. This is much more problematic. The higher incision also cuts across the lower abdomen and is very unattractive. A higher incision is less effective upon rejuvenating the mons area and can even result in a higher pubic hairline! Another way some surgeons deal with this is to sit the patient up while closing the waist crease incision, which will make the upper skin edge reach further down, but at the expense of putting the wound on much more tension during healing which will often result in a widened, obvious scar or even risk the wound separating or skin necrosis (death) at the wound edge. The patient will also not be able to stand upward for a considerable period of time which is uncomfortable. This is not an ideal way to manage the situation.

It is much better in these cases to just accept the little vertical scar. I can’t think of a single patient that has had an issue with this scar. Lastly, when the waist crease incision is being closed, a point is marked out on the abdominal skin flap just on top of the umbilicus. An ellipse of skin is removed and the umbilicus is brought out through that opening and sutured into place as the “new umbilicus” (really the old umbilicus).

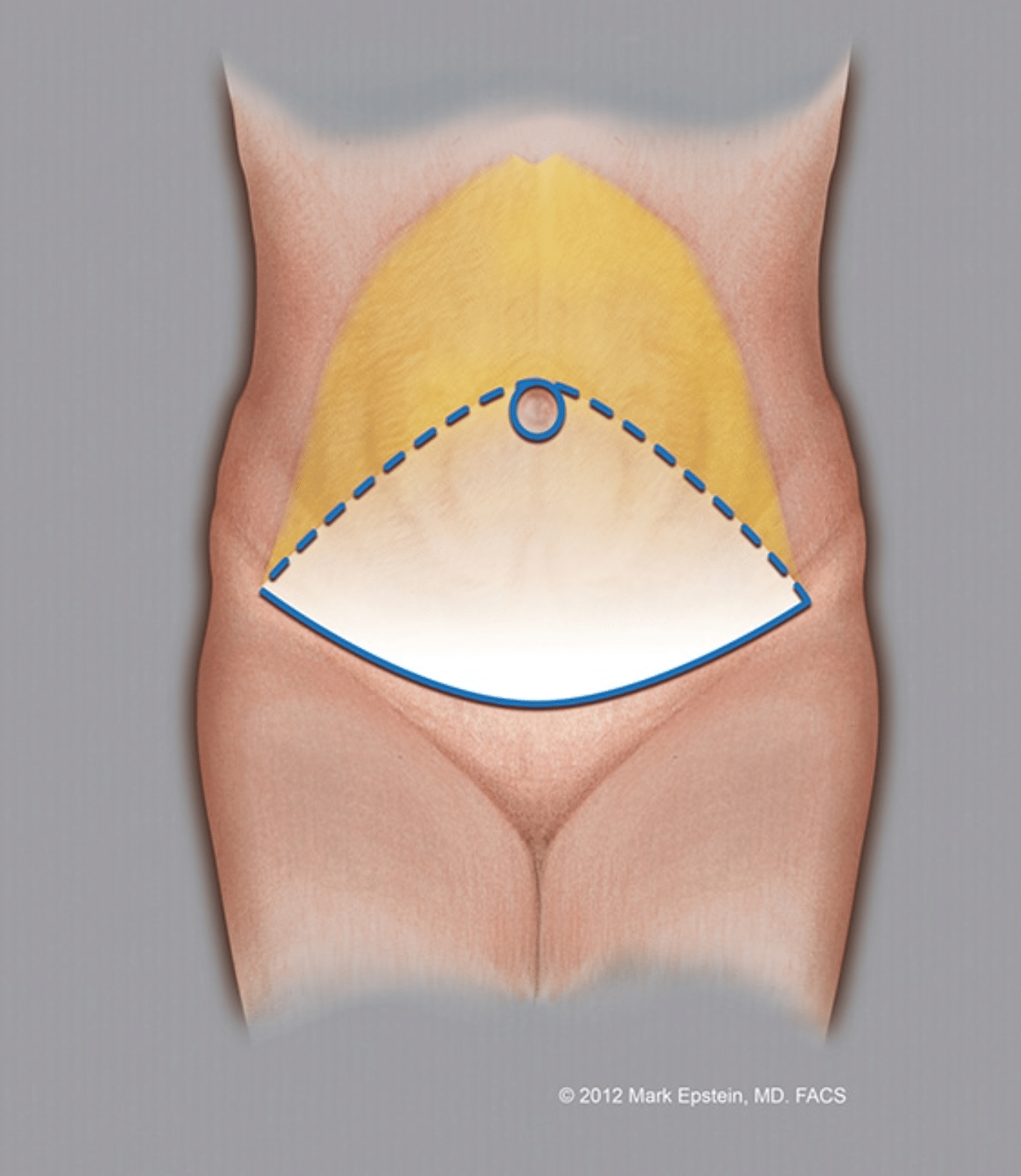

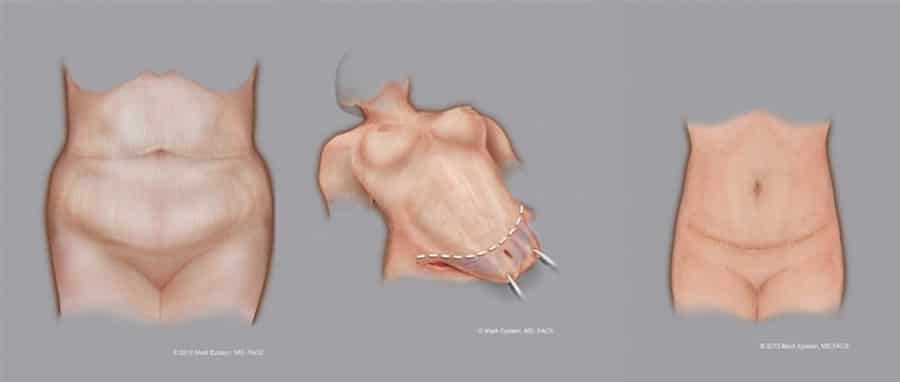

Figure 5A – Click to Enlarge

Figure 5A – Middle: Advancing the skin flap downward and removing the excess skin. There is enough upper abdominal skin excess to advance the excess skin downward far enough that the hole cut in the abdominal skin from around the umbilicus is now below the waist crease incision and will therefore be removed along with the excess skin. There is no need to close the hole because the hole is removed and therefore no vertical scar from its closure. Right: The final result is shown. The excess skin has been removed, a new hole was created on the abdominal skin flap and the umbilicus (which remained attached to the abdominal muscles below) is now brought out through that hole and sutured to that hole. Note the scar across the waist crease of the abdomen and around the umbilicus.

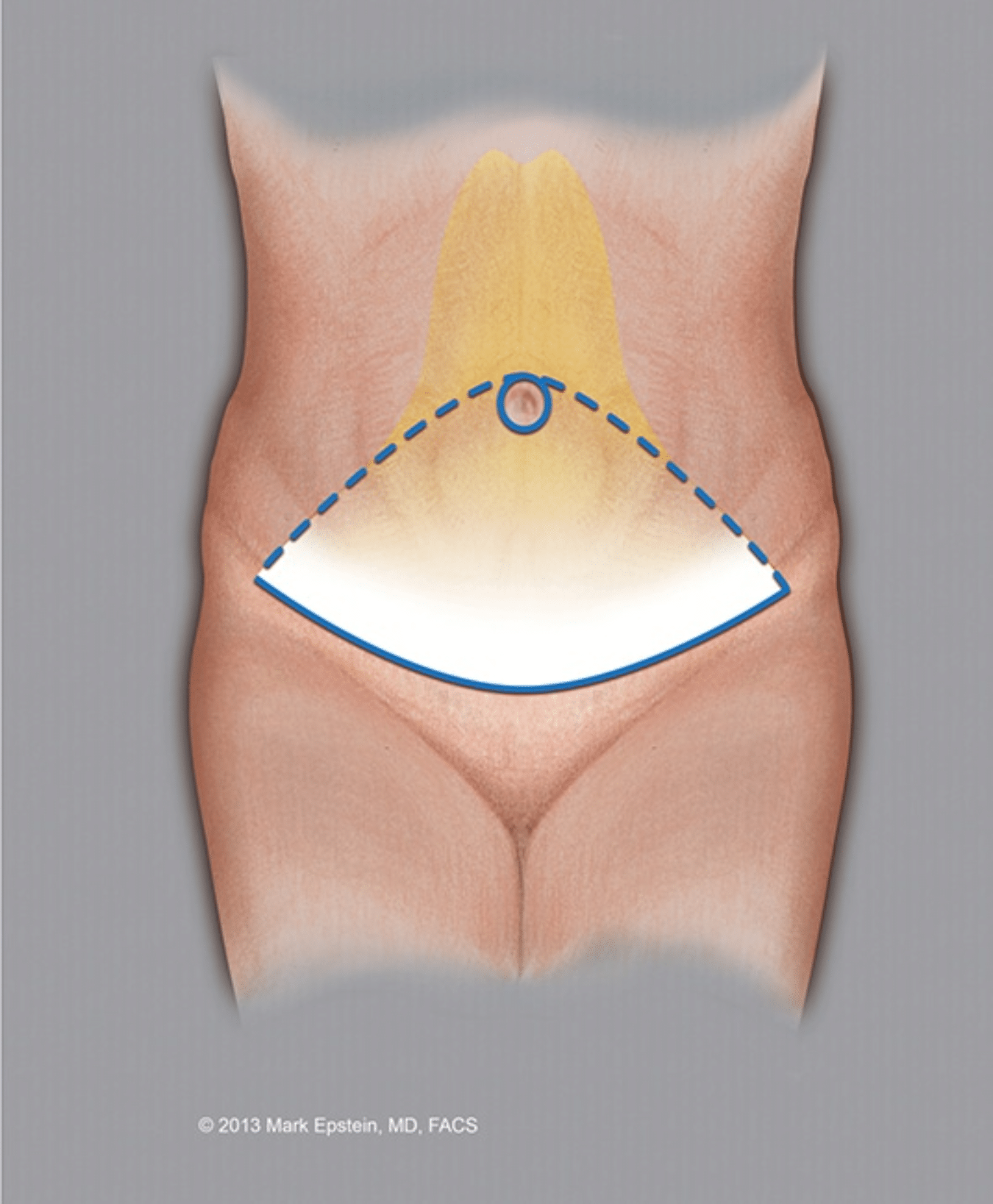

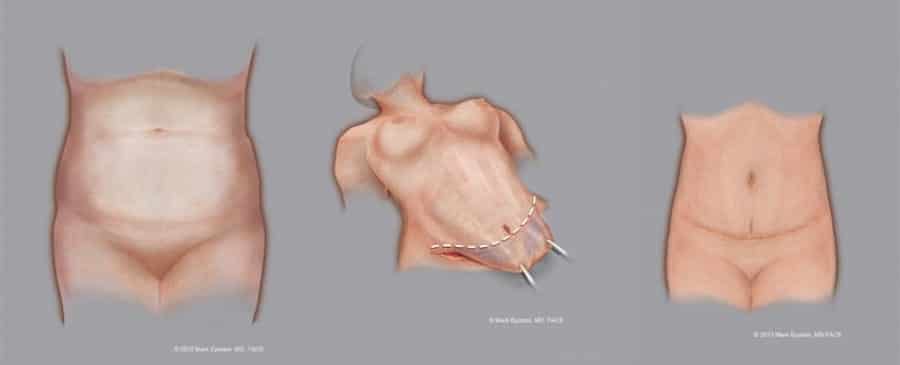

Figure 5B – Click to Enlarge

Figure 5B – Middle: Advancing the skin flap downward and removing the excess skin. There is not quite enough upper abdominal skin excess to advance the excess skin downward far enough so that the hole cut in the abdominal skin from around the umbilicus is now below the waist crease incision. The hole lies just above the waist crease incision and must therefore be closed in a vertical orientation. This will result in a small vertical scar lying just above and touching the waist crease scar as an “inverted T”. These scars are almost always not visible in clothing and bikini bottoms as the waist crease incision is intentionally made very low to begin with. Right: The final result is shown. The excess skin has been removed, a new hole was created on the abdominal skin flap and the umbilicus (which remained attached to the abdominal muscles below) is now brought out through that hole and sutured to that hole. The previous umbilical hole is now closed as a small vertical incision and lies just above the waist crease incision. Note the scar across the waist crease of the abdomen with the small vertical extension and the scar around the umbilicus.

Figure 5C – Click to Enlarge

Figure 5C – Middle: Advancing the skin flap downward and removing the excess skin. There is less upper abdominal skin excess than in the previous example. The hole will lie somewhere between the umbilicus and the waist crease incision and may be visible above the waistband of clothing or a bathing suit. Right: The final result is shown. The excess skin has been removed, a new hole was created on the abdominal skin flap and the umbilicus (which remained attached to the abdominal muscles below) is now brought out through that hole and sutured to that hole. The previous umbilical hole is now closed as a small vertical incision which now lies midway between the umbilicus the waist crease incision. Note the scar across the waist crease of the abdomen with the small vertical scar on the mid-lower abdomen and the scar around the umbilicus. In cases where there is very little upper abdominal laxity, sometimes a better choice is to “float the umbilicus” which avoids both scar around the umbilicus and the vertical incision on the lower abdomen altogether. The tradeoff is a slightly lower umbilicus, one without any scar around it, but this usually does not detract from the overall result of the procedure.

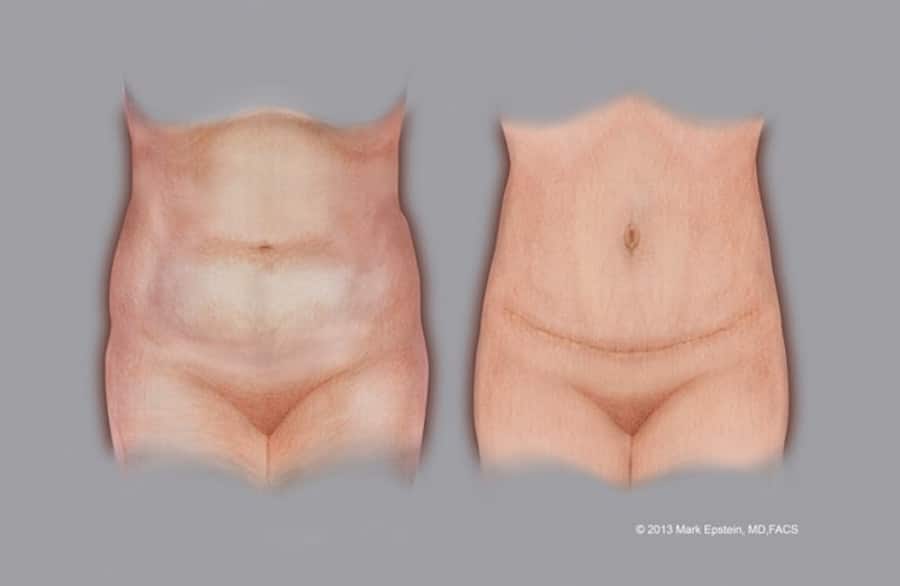

Figure 6 – Click to Enlarge

Figure 6 – Before and after abdominoplasty, showing the incisions

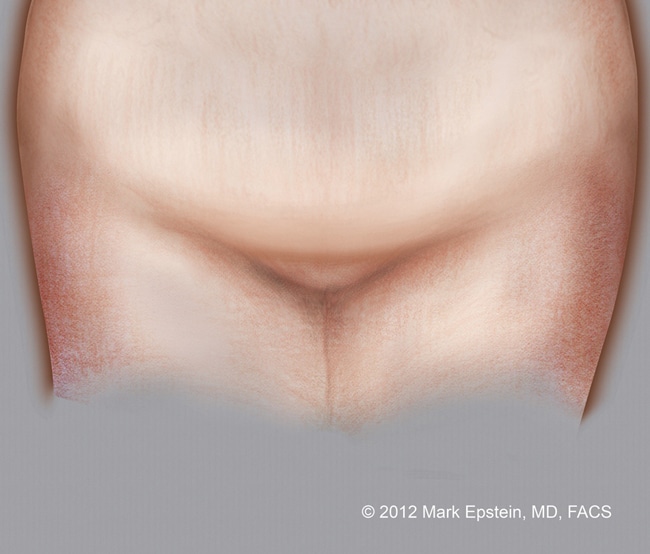

Rejuvenating The Mons

Often neglected in many abdominoplasties, the mons is an important part of the appearance of the abdomen, especially when the patient is undressed, but also it’s outline is often visible through tighter fitting clothing. At the lower border of the abdomen, under the influence of aging and weight gain, the mons area of skin stretches. As this happens the vertical height of the mons increases, and there often is a bulge in the center caused by excess fat and excess skin settling under the influence of gravity. In both males and females, this can result in covering of the genitalia to various degrees. In the female, the vulvar cleft (that vertical groove lying between the labia majora or the larger of the two sets of vertical lips of the genitals) can actually rotate downward and become partially obscured or even completely out of view as it faces downward rather than forward. This is a visual cue, that is to say, a subtle visual sign to the casual observer of an aging body, just as facial wrinkles are a visual cue of aging of the face. By removing excess skin of the mons when indicated, and planning the surgical incision appropriately to elevate the mons, and sometimes even coupled with some liposuction or direct excision of excess fat, the mons itself is also rejuvenated.

Figure 7 – How the mons ages, lengthening vertically and getting a central bulge, showing how the vulvar cleft rotates downward

Narrowing The Waistline

Narrowing of the waistline is the natural effect of removal of excess abdominal skin, tightening of the muscles and lastly how the upper abdominal skin is closed to the lower incision. In some cases, it is possible to bring the skin towards the center as the upper abdominal skin is sutured to the lower abdominal wound, also causing some narrowing of the waistline. Post operative garments such as abdominal binders do not do anything to narrow the waistline. 4D VASER Lipoabdominoplasty is much more effective at narrowing the waistline due to the removal of fat along the entire flanks, from the midline of the back all the way to the front of the abdomen.

Prev Chapter: What is an Abdominoplasty? »

Next Chapter: Drainless Abdominoplasty »